How Does African Culture Created Art Who Were the Nicolaitans

Chapter iv: The Impact of Religion and Bureaucracy on African Fine art

Chapter 4.ii Christianity and Art

Christianity's introduction to African occurred at wildly varying points in time, depending on the region, and its impact on the arts has been equally

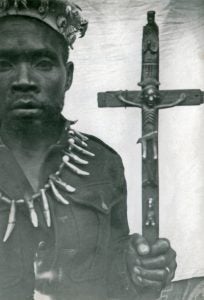

varied. It became of import in Egypt, the Sudan, and Ethiopia very early on, just equally it did in Europe. The residue of Africa, however, remained unaffected. When the Portuguese began to venture down the West African coast in the 15th century, they began a second wave of missionization (Fig. 578), which the French connected in the 18th century. These and other Catholic efforts were, however, geographically disjointed—although W, Primal, and southeast Africa were involved, high priestly expiry rates meant that Christianity ebbed periodically in selected coastal states until African clerics were ordained. Those states where it had the strongest touch on had monarchs who had converted (Fig. 579), such every bit many of the Kongo states, or were areas where the Portuguese or the Dutch created satellite communities.

More intense missionization waited until the 19th century, when Protestants joined Catholics in concerted efforts to catechumen Africans through both churches and schools. With trade expansion and colonization, evangelization moved inland and resulted in a widespread establishment of Christianity in many regions. African Catholic priests from multiple regions take themselves become missionaries to the U.s.a. and other international destinations, while Pentecostal denominations have established megachurch branches in European and American cities.

In general, Christianity has had a negative event on traditional religious art, although household appurtenances and other secular arts may accept remained unaffected. Missionaries often encouraged the destruction of objects relating to ritual practices, or collected such objects themselves to display in Europe when fund-raising for their efforts to convert the "heathens." In Ethiopia, withal, Christianity led to the establishment of key fine art forms that take been central to the fine art history of the Tigray and Amhara peoples. With a few key exceptions, Christian art elsewhere in Africa has been fairly limited.

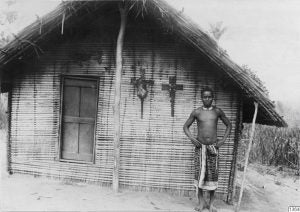

Sometimes it involves statuary produced for churches or devout individuals (Fig. 580), public statements of faith by the latter, or banners, plaques, or paintings fabricated for interior use (Fig. 581). Occasionally, religious references have cropped up in traditional art forms, such as crucifixion scenes every bit superstructures for Igbo maiden spirit masks. Christian forms and motifs take non, even so, replaced older art forms in number and types.

The almost visible expression of Christian art is church architecture. Colonists built structures in familiar styles (Fig. 582), oft in the rock that was standard in their metropoles, although a novel building material

in most of Africa. Near were designed past Europeans or Americans, but the Anglican Cathedral Church of Christ (Marina) in Lagos was designed by architect and engineer Bagan Benjamin, a "Saro" (a Liberated African who came to Nigeria from Sierra Leone), albeit afterwards a European model. Begun in 1925 and completed in 1956, its simplified neo-Gothic manner includes flying buttresses and pointed arches, but lacks the spires that would relieve its visual heaviness. Penned in today by high-rises, information technology one time served every bit a waterfront focus, soaring above nearby buildings in a statement of colonial Christian potency.

Catholic churches continued the decorative programs–sculpture, painting, textiles–that it had long commissioned, while Protestants continued to abjure well-nigh figurative ornamentation. As the 20th century advanced, locally designed churches became more than internationally modernistic in style, unremarkably abandoning stone in favor of reinforced physical or cement. Pentecostal Protestant churches range from the modest to the enormous (Fig. 590), the latter stressing streamlined design over decoration.

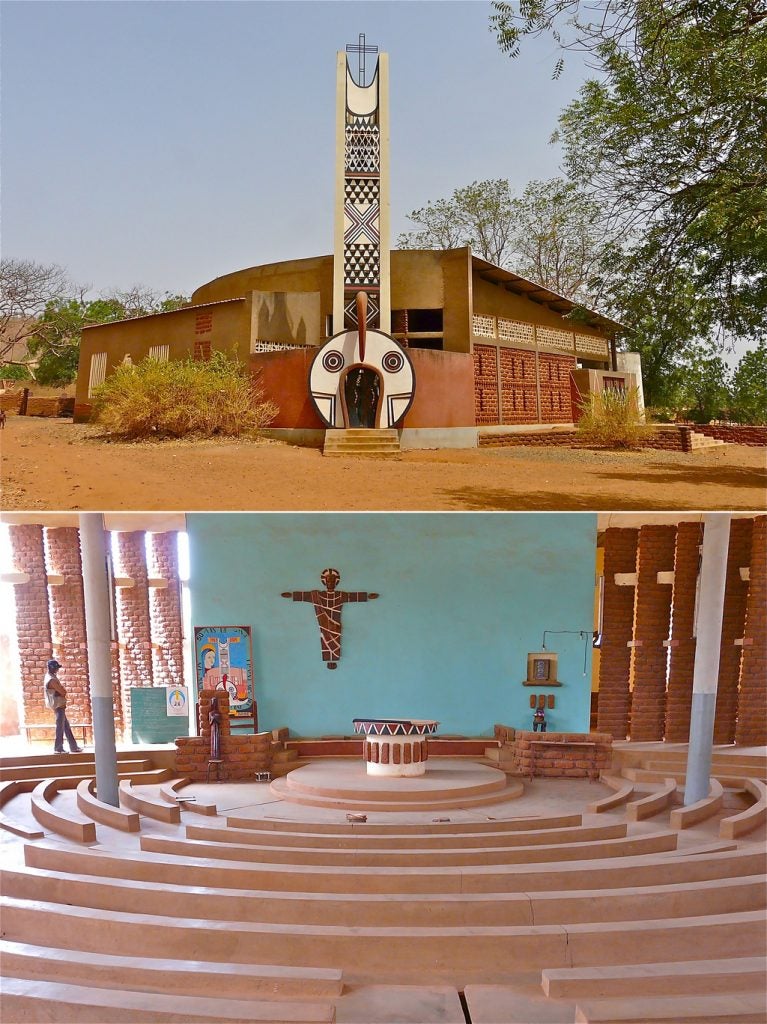

The second half of the 20th century saw foreign missions erect a number of Cosmic churches that departed from Western designs. Instead, they co-opted traditional symbols and materials in an effort to indigenize the physical Church (Fig. 591), frequently involving traditional artists in their construction and decoration (Fig. 592).

Subsequent post-independence architecture tended to adhere to the International Fashion of sleek concrete compages, but some artists took directions that were out of the mainstream. Beginning in the 1960s, Demas Nwoko designed and supervised the erection of St. Thomas Aquinas Priory, a chapel complemented past a lounge, school, and refectory for the Dominican order in Ibadan, Nigeria (Fig. 593). Hailed for its originality, its use of cross-shaped lighting is reminiscent of Le Corbusier, but a partial moat, outside screening elements, and carved wooden interior posts combine to create a distinctly African variety of Modernism, an achievement matched by few other buildings.

Individual missionaries sometimes took the initiative to become more sustained patrons, such as Father Kevin Carroll, a Society of African Missions priest who worked in the Oye-Ekiti region of Western Nigeria. From 1947–54, Carroll led a

workshop that enlisted traditional Yoruba sculptors–many of whom were Muslim–to carve doors with Christian themes that followed the organization and style of Yoruba palace doors, as well as various objects such as baptismal fonts, Stations of the Cross, and Nativity scenes. These bandage Biblical characters in familiar Yoruba modes: the Declaration shows the affections actualization to Mary as she pounds in a mortar, ane of the Magi brings his gifts in a kola nut container.

As the century wore on and almost Catholic missionaries were replaced past African missionaries, additional churches both incorporated elements that reflected local culture (Fig. 594) and, in an endeavour to testify their international outlook, replicated famous European religious sculpture.

Extant Christian sculpture in Africa dates back to Lalibela reliefs (see below). In W Africa, Christian references first appeared on a number of ivories from Sierra Leone carved for the Portuguese. These delicate objects included several pyxes meant for ecclesiastical use, covered

with scenes from the lives of Christ or the Virgin Mary, but even secular items such as saltcellars meant for an aloof table might include Christian motifs to demonstrate either a family's devotion or that of a high-ranking cleric (Figs. 595 and 596). The forms of the objects frequently mimicked European cups, and in some cases–like this–foreign prints were apparently shown to the artists.

Once colonization and intensive missionization began, more than sculptors and painters began incorporating Christian missionaries and Biblical subjects in their work, either as local observations or deputed work (Fig. 597). Sometimes these were totally new inventions that adhered to European representational modes, but at other times interpretations referenced traditional fine art. Amongst the Ibibio of Nigeria, for example, the course of the traditional girl's doll was adapted to become that of Christ on the cross (Fig. 598).

As time went on, both Christian urban and academic artists included religious themes in their repertoire. Some of the former, such as Chéri Samba, have critiqued money-mongering preachers in their work. Others, like Omnipotent God (Kwame Akoto), had personal religious revelations and

refer to Christianity in paintings that range from depictions of Christ (Fig. 599) to admonitions to stop smoking.

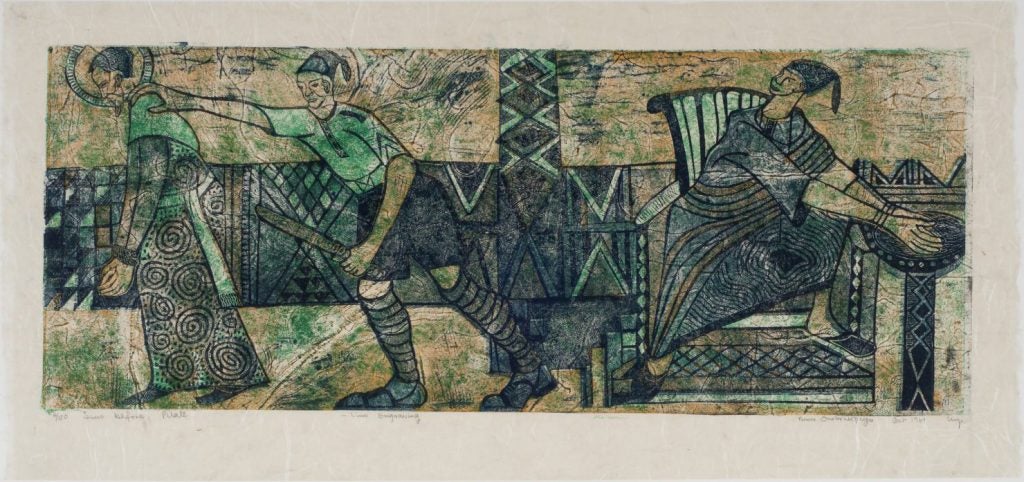

Academic artists such as Bruce Onabrakpeya, who also examines cultural and historical themes, have besides addressed Biblical subjects. Onobrakpeya'southward linocut xiv-print series, Stations of the Cross, creates a sense of immediacy to his Nigerian audience by incorporating local references, as European artists have washed for centuries. When Christ meets his mother, she wears the ikele coral circlet and okuku beehive hairstyle of the Benin Kingdom court. Some members of the crowd along the crucifixion's procession are dressed in Yoruba patterned indigoadire cloth, and the Roman soldiers habiliment the uniforms of Hausa members of the colonial British police (Fig. 600), an indictment of both the former oppressors and their agents and a possible coded reference to Nigeria'south divisive legacy during the contemporaneous civil war.

Coptic Christian Art

Egyptian traditions state that St. Mark brought Christianity to Alexandria in the starting time century CE, and it spread due south in the second century. It became Nubia'due south official religion in 580 CE, and was heavily influenced past the Byzantine Empire. Ethiopia, which had had a long-standing relationship with Israel and already had a Jewish segment of the population, evidently housed some Christians past the first and 2nd centuries, and, past the quaternary century Frumentius, a Syrian-Greek who was enslaved in Ethiopia's Axum Kingdom, began to make converts, including the king. Frumentius traveled betwixt Alexandria and Axum, and from the latter, the faith spread quickly as the state religion. Byzantium and the Mediterranean earth more generally traded and interacted with both Nubia and Axum, and afterward with other Ethiopian capitals, and the Christian art of Ethiopia shows the influence of successive trading partners: the Greeks and others from Byzantium, the Italians and Portuguese of the 15th-17th centuries, and even the Indians of the 18th century. Coptic Christianity is distinct from both Catholicism and Eastern Orthodox religions, although it has considerable affinities with both. Ethiopia's official liturgical tongue is Ge'ez, a Semitic linguistic communication that is no longer spoken outside church services.

The appearance of Islam somewhen brought an end to Nubia's Christian faith with invasions from Egypt that lasted from the 7th century to 1504. At its

meridian, however, numerous churches and monasteries were clustered near the Nile in the kingdoms of Alwah, Makuria, and Nobatia. After the Islamic conquest, most fell to ruins, and some were covered past earth and forgotten. While Arab republic of egypt was planning to build the Aswan Dam forth the Nile, archaeologists came to the surface area to perform emergency excavations, since the resultant dam would produce a lake that would cover a huge area–and did, upon the dam's 1970 completion. Some structures were relocated, others submerged; still others were unknown until the archeological teams explored the expanse. Ane of the surprises occurred in the rich trading town of Faras, a medieval Nubian city at present in Sudan and once Nobatia's majuscule. Preliminary observation suggested a large mound might exist a temple site, but excavations revealed it was the Cathedral of Faras. Congenital in the early 7th century, subsequent versions were erected on its foundations. The

building's foundation was stone, with its upper levels fabricated of fired brick; its interior included several refurbishments that closed in some of the spaces spanned by vaulting (Fig. 601).

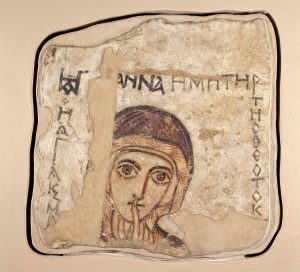

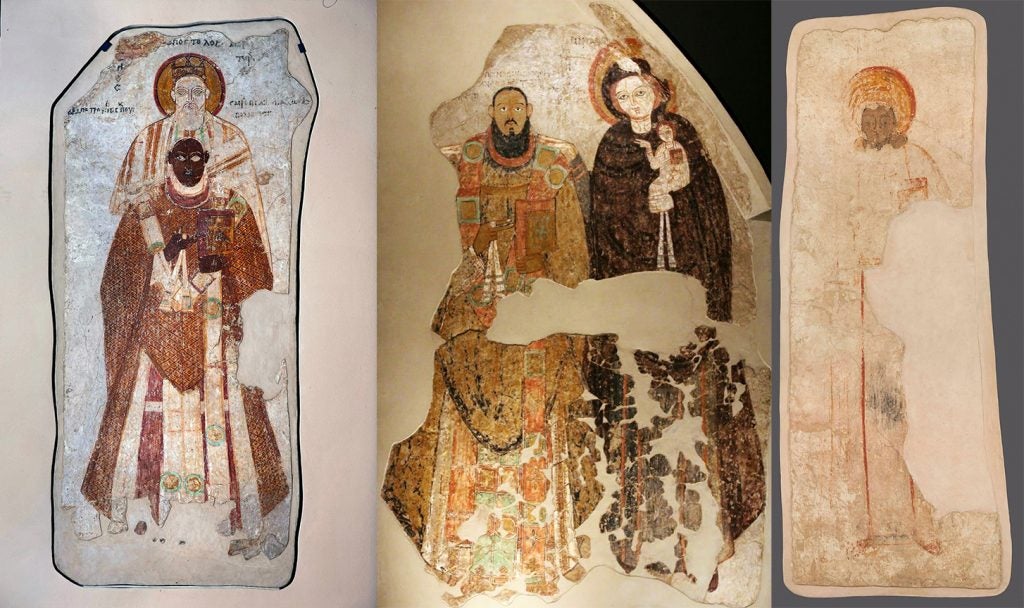

Its frescoed walls were added to until the 14th century and include numerous paintings of Biblical and saints'

scenes. These follow the mode of Byzantine fine art: backgrounds are plain or simplified, naturalistic anatomy is discarded in favor of flat, elongated robed figures that stress patterning, figures are unremarkably frontal with stylized linear features that emphasize the eyes, long narrow noses, expressive hands, and stylized drapery folds (Fig. 602). Several images show Nubian loftier-ranking clerics and royals in the protective presence of saints, their tunic textiles following Byzantine fashions; saints are themselves

oft dressed more modestly (Fig. 603).

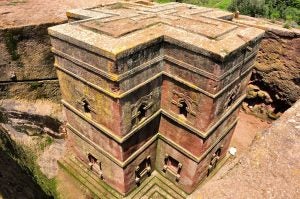

By the 4th century, the ruler of the Axum kingdom in Federal democratic republic of ethiopia became a Christian convert, and it became a state religion. Additional missionaries spread the religion into the Tigray region, and numerous churches and remote monasteries were built, some in caves and partially cut into the rock. The almost spectacular structures are a serial of 11 churches said to accept been congenital past Emperor Lalibela in the boondocks now named for him (Fig. 604); angels are said to have worked on the buildings at night, afterwards man workers slept. While some scholars believe the timespan for their construction may have begun several centuries before, there is no business firm evidence as to how long it continued. A few structures may have showtime been used as fortresses or palaces, their purpose changing over time, while other areas show abandoned attempts at construction.

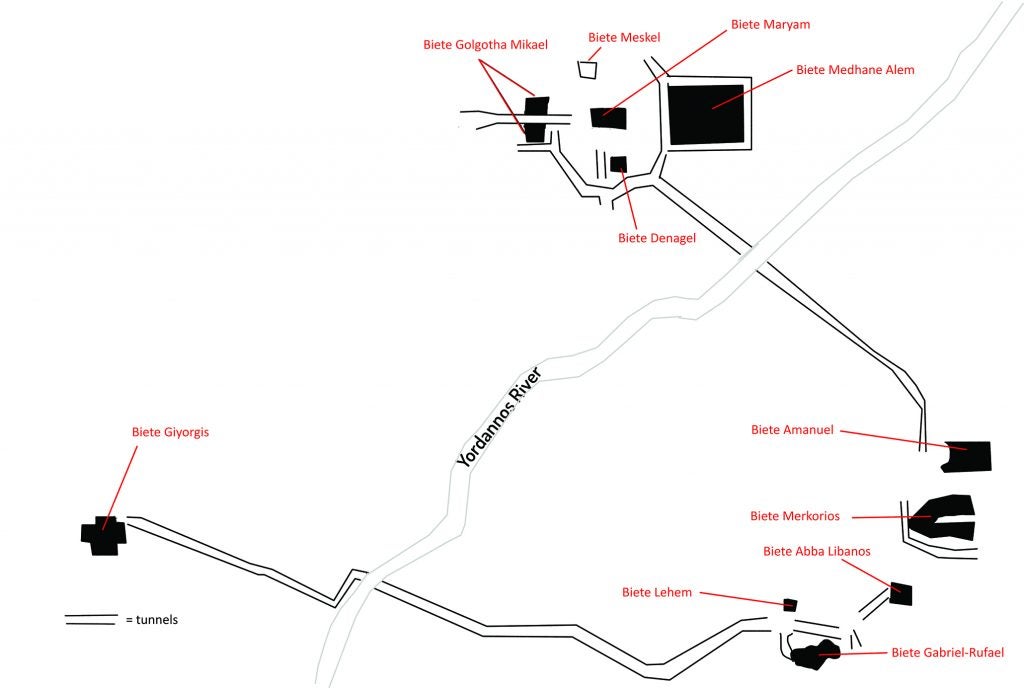

Lalibela, whose reign is encircled in myth-like tales, is said to have had a dream in which he envisioned the churches, which he conceived of as a pilgrimage alternative to Muslim-occupied sites in Jerusalem. His New Jerusalem is divided by a river referred to equally the Jordan (Yordannos), and nearly of the churches on either side are interconnected by underground tunnels (Fig. 605).They are amongst very few monolithic buildings worldwide; that

is, each is made of a single huge stone that had to be hollowed out to form an interior. Commencement the surrounding stone had to be gradually removed; when a window was created, it opened the opportunity to tunnel in and carve out the interior.

Although all but ane church building has a rectangular exterior, simply some interiors take that shape, while others are cruciform. Imitative architectural forms demonstrate awareness of other buildings. One imitates Axum structure (as the Axum stele did themselves), with projecting mock beams supporting recessed layers of rock and mortar, while others incorporate false arches and fifty-fifty a dome–neither of which actually performs the part of distributing the thrust of the stone equally true arches and domes are able to do. The technology knowledge to create these massive structures is remarkable, for, while some bear witness repairs, none collapsed upon themselves. Earthquakes and water harm take necessitated a programme of restoration, aided by the churches' status equally a UNESCO Earth Heritage site. They remain the focus of pilgrimages, specially full at Orthodox Christmas and at Timkat, the Epiphany celebration.

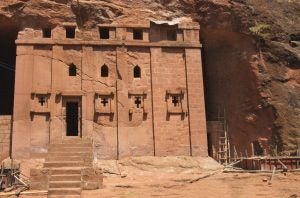

No two churches have identical forms. Many are partially congenital into the surrounding rock, such as Bete Abba Libanos (House of Abbot Libanos) (Fig. 606), which is attached to the living stone at the roof and floor level. Others, however, are free-continuing, such as Biete Maryam, or the Firm of Mary (Fig. 607).

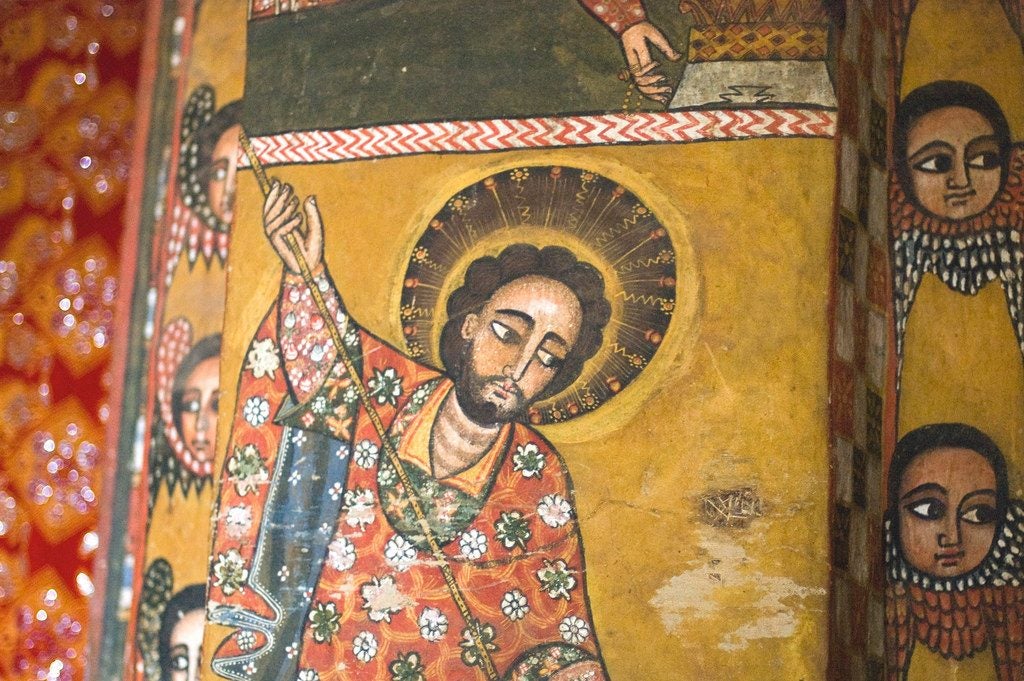

Over its primary entrance stands the image of two horsemen hunting a dragon (Fig. 608), a scene that may relate to St. George the dragon killer, for he is the patron saint of Ethiopia and appears ofttimes in its art. It has three thrusting porch entrances, and, similar most of the Lalibela structures, few windows, which produces a dim interior, formerly lit but past candles. Biete Maryam'south interior boasts intricate painted geometric relief carving on its walls and arching openings (Fig. 609). A courtyard puddle is meant to help infertile women excogitate.

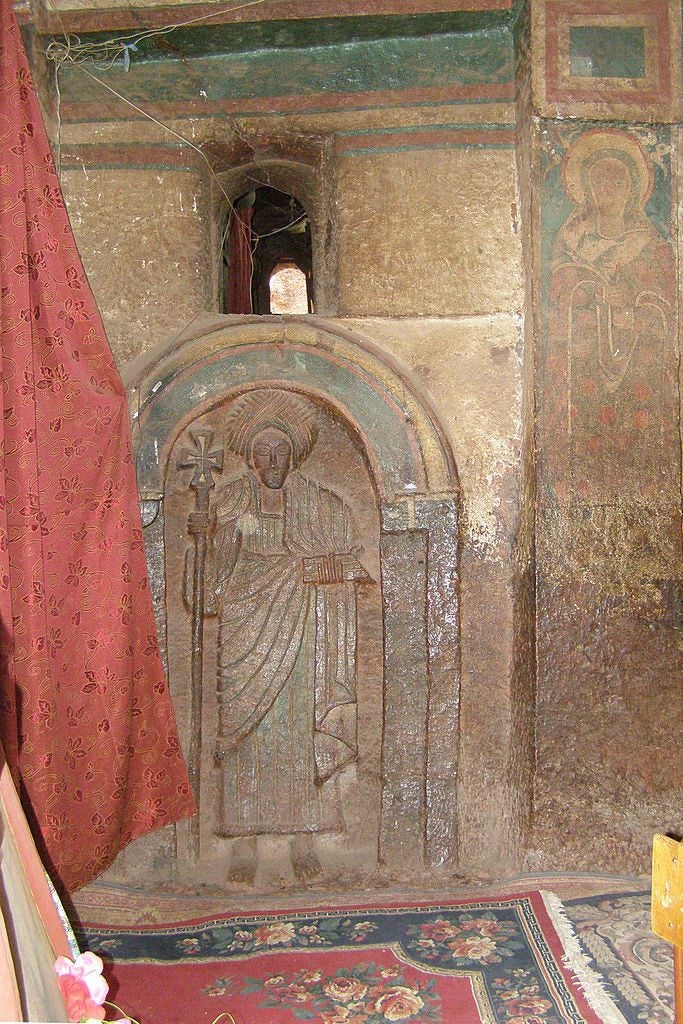

Biete Golgotha, the merely Lalibela church barred to women, includes seven large figurative reliefs of saints gear up inside rounded, arched niches (Fig. 610); a panoramic view of its interior can be viewed here. Some of the saints conduct halos, while others wear the turbans notwithstanding seen on priests locally. The rigidly engraved lines that marker the folds of their dress follow Byzantine conventions.

Biete Gyorgis (St. George's Business firm) is the only isolated church building at Lalibela, and can only be accessed through tunnels and inclines. Its distinctive cross-shaped exterior (Figs. 611 and 612) has a apartment roof inscribed with concentric crosses, simply on its within, a fake dome has been hollowed into the ceiling, again indicating awareness of stone architecture from other parts of the world.

Highland Ethiopia'south adherence to Christianity and its position as a state organized religion continued among the Amhara who ruled from a serial of capitals. A seemingly infinite variety of cantankerous shapes were used liturgically in both wood and metallic, many as cast processional crosses mounted on wooden poles. Sure examples display radial symmetry (Fig. 613), while others (Fig. 614) include engraved designs influenced past 15th-century Italian imagery, despite their compressed proportions and simplified linear way. Missionary travel brought numerous Italians to the imperial court at that fourth dimension, a period when Marian imagery became office of court devotion. At least ane Venetian painter, Niccolò Brancaleone, settled in Federal democratic republic of ethiopia, working ca. 1480-1520, and trained students.

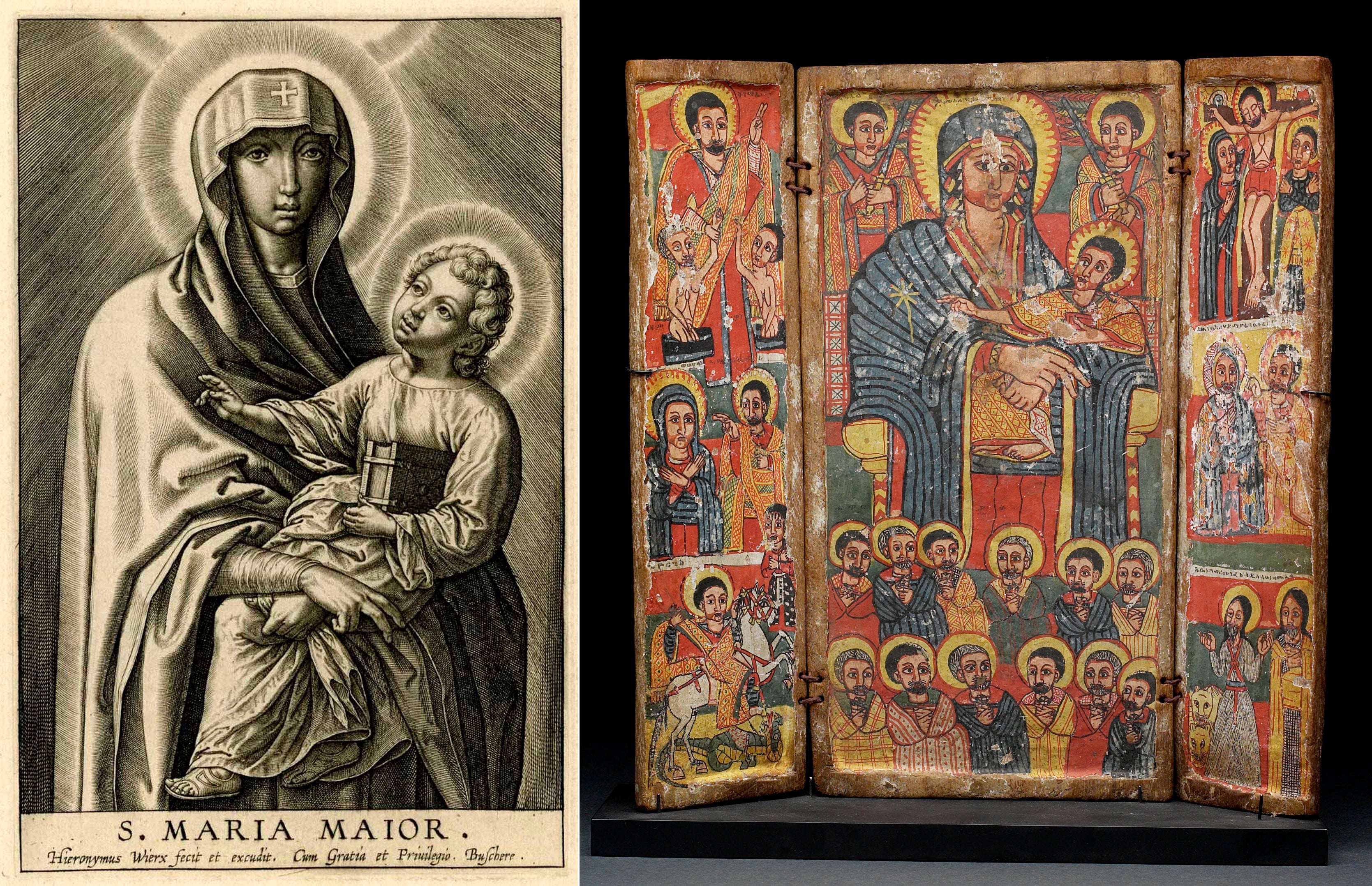

Even without direct contact, prints exposed Ethiopian artists to European religious works, although their influence was primarily compositional an iconographic, rather than stylistic. Early 17th-century Jesuit missionaries circulated prints of the Madonna based on a 6th-century icon from a Roman church felt to have miraculous backdrop; the painting's composition had already been copied in many Roman churches. Ethiopian painters added their own touches (Fig. 615), taking a single image and transforming it into a triptych, adding angels and the apostles (shown in hieratic scale) to the main scene, and including St. George, as well equally Biblical scenes, on the side panels. This became a stock epitome for portable devotional imagery–admitting with considerable variation, such every bit patterned textiles or the occasional inclusion of a cowrie-crush necklace around Christ's neck. Most noticeably, notwithstanding, Ethiopian artists rejected the naturalism of the print, irresolute the head-to-body proportions and favoring unrealistic linear depictions without the shading that provides the illusion of three-dimensionality.

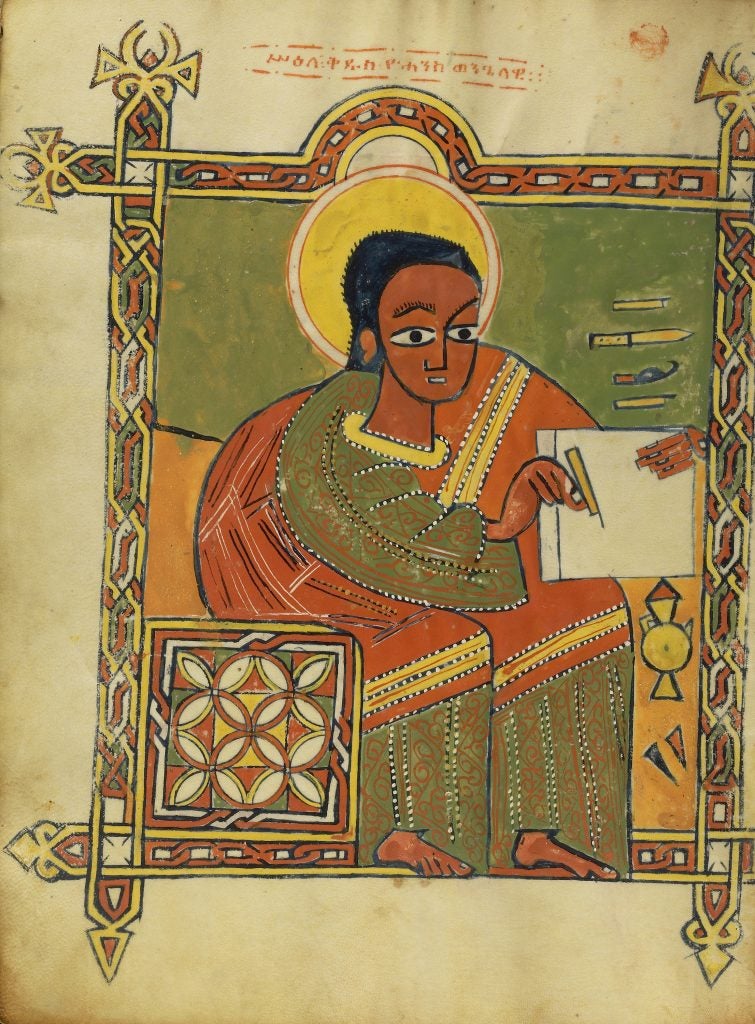

Fresco painting on church building and monastery walls and ceilings (Fig. 616), as well as illuminated manuscripts (Fig. 617), provided monk-artists with scope for images that continued to stress decorative borders and patterning with stylized figurative representations.

Subject matter in Ethiopian fine art remained wholly Christian-oriented until the 1ate 19th century, when some battle scenes were produced; although genre images accept entered pop imagery and academically-trained artists create abstruse works (Fig. xxx), Christian discipline matter still dominates.

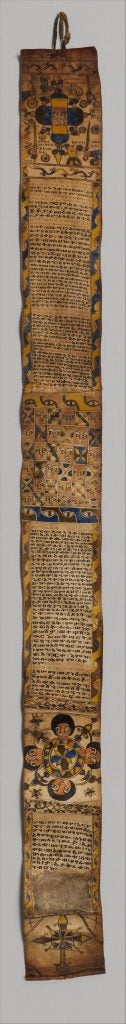

One standing tradition involves a magico-religious employ of art in the form of talismanic scrolls. If an individual falls ill, the family may call in adebtera, an unordained cleric who specializes in curative rituals, despite the fact the official

Church frowns on these practices. Beliefs aspect many illnesses to evil spirits, and art is used to help exorcize them by calling on the underground names of God, request for saints' intercessions, and compelling demons to obey. The debtera takes a goat or sheep and rubs it against the patient. The animal is then sacrificed, its peel treated until information technology becomes a parchment scroll that matches the patient'southward height (Fig. 618). It is then inscribed with prayers and illuminations specific to the illness. Angels with raised swords populate many scrolls, as practise abstract configurations reminiscent of magic

squares (Affiliate 4.3) meant to activate divine powers of protection. Some of these emphasize optics

(Fig. 619); the patient and demon expect at each other until the latter is entrapped and expelled. After healing, the scroll is rolled up and placed in a leather container, worn effectually the former patient's cervix.

The many varieties of crosses even so show up on Ethiopian jewelry, worn as necklaces past women (Fig. 620), just too appearing on mundane articles, such as implements to clean ear wax (Fig. 621). This Christian symbol acts non only as a symbol of piety, merely a motif that offers protection. It appears on the embroidery of women'southward white gowns, and fifty-fifty as facial tattoos (Fig. 622).

Further Reading

Akinola, Olatubosun. "Influences of Catholic Mission on Yoruba woodcarving." In Christoph Elsas and Hans-Hermann Münkner, eds.Selected essays on the occasion of the 90th anniversary of Ernst Dammann, pp. 78-82. Berlin: Verlag Dietrich Reimer, 1994.

Appleyard, Jed. Ethiopian manuscripts. London: Jed Printing, 1993.

Bassey, Nnimmo. "Demas Nwoko's compages." In Udechukwu, Obiora, ed.Ezumeezu: essays on Nigerian art & compages: a Festschrift in honour of Demas Nwoko, pp. 165-178. Glassboro, NJ: Goldline & Jacobs Pub., 2012.

Bridger, Nicholas J. Africanizing Christian art: Kevin Carroll and Yoruba Christian art in Nigeria. Cork, Ireland: Guild of African Missions, 2012.

Carroll, Kevin.Yoruba religious carving: pagan & Christian sculpture in Nigeria & Dahomey. New York: Praeger, 1967.

Chojnacki, Stanislaw.Ethiopian crosses: a cultural history and chronology. Milan: Skira, 2006.

Curnow, Kathy. "The Afro-Portuguese Ivories: Classification and Stylistic Analysis of a Hybrid Fine art Class." Ph.D. dissertation, Indiana University, 1983.

Finneran, Niall. "Built past Angels? Towards a Buildings Archaeology Context for the Rock-Hewn Medieval Churches of Ethiopia."World Archaeology 41 (3, 2009): 415-29.

Gnisci, Jacopo. "Crosses from Ethiopia at the Dallas Museum of Art: an overview."African Arts 51 (4, 2018): 48-55.

Godlewski, Włodzimierz. "Some remarks on the Faras Cathedral and its painting."Journal of Coptic Studies 2 (1992): 99-116.

Godwin, John and Gillian Hopwood. The Compages of Demas Nwoko. Lagos: Farafina, 2007.

Heldman, Marilyn Eiseman. "Architectural symbolism, sacred geography and the Ethiopian Church."Journal of Religion in Africa 22 (3, 1992): 222-241.

Mercier, Jacques.Ethiopian magic scrolls. New York: G. Braziller, 1979.

Quarcoopome, Nii O., ed. Through African eyes: the European in African art, 1500 to nowadays. Detroit: Detroit Constitute of Arts, 2010.

Ross, Doran H. "The Art of Almighty God." African Arts 47 (2, 2014): 8-27.

Silverman, Raymond Aaron, ed. Federal democratic republic of ethiopia: traditions of creativity. Eastward Lansing: Michigan Country University Museum/Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1999.

Kongo Catholicism

The Kongo region in Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo and the Republic of Congo felt the impact of European missionizing in the late 15th century, eight years after the Portuguese get-go reached the coast of Central Africa. Quickly, the Kongo ruler and many members of the royal family and courtroom were baptized, and afterwards the name of the capital letter metropolis, Mbanza Kongo, was recast equally São Salvador.

The Portuguese congenital a small-scale church building defended to the "Holy Saviour of Congo" in 1591, which was afterwards rebuilt and expanded into a white-washed stone cathedral (Fig. 623). Many churches were erected over royal cemeteries, although Christian burials in and outside churches remained elite privileges. Majestic chapels within churches became sites that allowed ancestral cults within an approved context.

In 1509, the first Christian monarch's son, Affonso I, ascended the throne after a tearing battle with a rival one-half-brother–a boxing in which he stated that St. James led his troops to victory. After his installation, adherence to Christianity intensified for all those who sought his favor. He quickly commanded provincial rulers to erect a church and a monumental cantankerous in their local capital's public plaza, overt statements of a land organized religion. Affonso had been mission-trained and corresponded with the Pope, and sent one of his sons to Portugal, where he entered the priesthood and became the kickoff Catholic bishop from sub-Saharan Africa. Affonso ordered nkisi and other traditional religious items in the capital destroyed, simply the church he championed included syncretic elements that overlapped traditional religious conventionalities and seem to have made Christianity more acceptable. Kongo religion's High God, Nzambi a Mpungo, is considered the Creator and was conflated with the Christian God. The shape of the cantankerous itself had strong internal meaning (see Chapter 3.v). Strong beliefs in the powers of ancestors and the spirits of the expressionless transferred to those of saints. While various orders of European missionaries continued to visit the Kongo kingdoms over the centuries, they were supplemented past local clergy and, more frequently, past elite lay instructor-ministers known as mestres ("masters"). While everyone in the kingdom was certainly not a Christian, and many Christians besides practiced elements of traditional organized religion, Christianity had a broad bear upon, particularly among the elite.

Over the centuries, missionaries imported many crucifixes, but Kongo artists supplemented these with local bandage-contumely or brass-on-forest examples (Fig. 624). Although museums date these works, it is difficult to distinguish their dates of origin with certainty. Some are closer to European models than others, with more naturalistic head-to-body proportions and accurate anatomy (upper left, Fig. 624). Others overstate the head, depict Christ's eyes through a java-bean abstraction, transform His projecting ribs into a kind of scarification, and enlarge and flatten His hands and feet. Even those figures, even so, almost always tilt the head of Christ in the fashion of European imagery. Additional figures–saints? angels? supplicants?–often occupy extensions of the crucifix, its base frequently begetting an abstracted figure of the mourning Virgin. One example (Fig. 625) includes the additional crucifixes of the thieves executed adjacent to Christ by stacking them in a higher place and below his portrayal, rather than flanking him. He remains considerably larger than them, an example of local hieratic scale trumping naturalism.

Statues of saints and the Madonna also appeared in Kongo art, with the Portuguese Saint Anthony of Padua prominently featured (Fig. 626). Born in Portugal, the saint's appeal was probably boosted by those missionaries who were themselves Portuguese. A royal church named after the saint stood in the Kongo capital, and an aristocratic religious confraternity–a non-clerical organization that organized members' burials, participated in saints' solar day processions, staged devotional performances, and promoted charitable acts–besides bore his proper noun; information technology was one of half-dozen confraternities in the belatedly 16th-century capital. St. Anthony's popularity in the Kongo Kingdom was probably less due to his association with finding lost objects and securing husbands for maidens than it was with his power to bring children to barren women, relating every bit it does to a critical cultural desire. In European art, St. Anthony is often depicted with a lily that represents purity, with a Bible, or with the Christ Child seated on a Bible he holds. In Kongo fine art, this concluding-mentioned motif sometimes depicts Christ sitting or standing on a Kongo box throne, belongings a flywhisk equally a mark of kingship. In the 18th century, St. Anthony took on boosted political meaning. The unified Kongo Kingdom had broken downward in the 17th century, with civil wars resulting in independent states. A purple woman, known by her baptismal name as Dona Beatriz (ca. 1684-

1706), joined a Kongo group who went to settle in the old royal capital, which had been abandoned. Discipline to visions, she referred to herself as the reincarnation of Jesus Christ and created a variation of Catholicism chosen Antonianism, whose goal was to recreate a unified and Christian Kongo Kingdom under her leadership. As her followers grew, established regional monarchs grew uneasy. She was captured, tried, and convicted of witchcraft, followed by execution.

The association of Christian symbols with political and healing powers continued, even in those

eras where Catholic influence waned. Some aristocrats were buried with cross-shaped markers (Fig. 627). In other areas, rulers or distinguished chiefs held staffs of function that might include a cantankerous or a saint'due south figure (Fig. 628). These originated as a badge of office for the mestres, and were called santu-spilitu, a localized term for the Latin phrase for the Holy Spirit. Topped by a cross, they could be inserted into the footing

during judicial proceedings, human activity as an envoy's bluecoat of identification, or mark the site of ritual activeness.

Both civil authorities and ritual specialists might own crucifixes as badges of power or

healing (Figs. 629 and 630), alongside more traditional forms of nkisi (meet Affiliate 3.five). Other cross forms, sometimes known as santu, became associated with adept fortune in hunting (Figs. 631). These are sometimes fastened to nkisi bundles filled with additional medicines. Their forms are not identical to that of a common Christian cross; they oftentimes have cutting-outs, notches, or additional

projections (encounter Figs. 632 and 633). In the early 20th century, they were said to have been blest by a priest before a hunting expedition, and so a few drops of the casualty's blood would be dripped onto the hole in its middle.

Although the 19th century and colonialism saw the conclusion or alteration of many centuries-old Kongo Christian practices, new missionary orders emerged from the Catholic "motherlands" of Belgium, Portugal, and French republic, as did Protestant denominations that abjured statuary and crucifixes. Many churches of varied origins stand in the Kongo territories of the Republic of Congo, Angola, and the Democratic Republic of Congo today, including Mormon temples and both small and gigantic Pentecostal structures, Catholicism remains the dominant sect, professed by at least half of the population of the three countries. While some earlier churches are still in use, others are contemporary buildings that reflect irresolute tastes (Fig. 634).

Farther Reading

Felix, Marc Leo, et al.Gangguo Wangguo de yi shu = Kongo Kingdom fine art: from ritual to cut edge. Xianggang: Wen zu yi shu yu wen hua you xian gong si, 2003.

Fromont, Cécile.The art of conversion: Christian visual civilisation in the Kingdom of Kongo. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Heimlich, Gregory. "The Kongo cantankerous across centuries."African Arts 49 (3, 2016): 22-31.

Heywood, Linda Grand. and John 1000. Thornton.Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles, and the foundation of the Americas, 1585-1660. New York : Cambridge University Press, 2007.

LaGamma, Alisa, et. al.Kongo: Power and Majesty. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015.

Massing, Jean Michel. "Crosses and Hunting Charms: Polysemy in Bakongo Religion." In Encompassing the Globe: Portugal and the World in the 16th and 17th Centuries: Essays, ed. Jay A. Levenson, 87-96. Washington, DC: Arthur One thousand. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Mello eastward Souza, Marina. "Central African Crucifixes: A Report of Symbolic Translations." InEncompassing the Globe: Portugal and the World in the 16th and 17th Centuries: Essays, ed. Jay A. Levenson, 97-101. Washington, DC: Arthur Thousand. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Slenes, Robert W.Saint Anthony at the crossroads in Kongo and Brazil: "creolization" and identity politics in the black south Atlantic, ca. 1700-1850. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2008.

Thornton, John 1000. "Afro-Christian Syncretism in the Kingdom of Kongo."Journal of African History 54 (i, 2013): 53-77.

Thornton, John K.The Kongolese Saint Anthony: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian motion, 1684-1706. New York : Cambridge University Printing, 1998.

Volper, Julien.Du Jourdain au Congo, art et christianisme en Afrique centrale = Crossing rivers: from the Hashemite kingdom of jordan to the Congo: art and Christianity in Central Africa. Paris: Flammarion, 2016.

zimmermanyoult1971.blogspot.com

Source: https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/bright-continent/chapter/chapter-4-2-christianity-and-art/

0 Response to "How Does African Culture Created Art Who Were the Nicolaitans"

Post a Comment